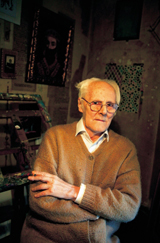

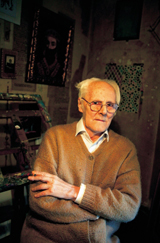

Mário Cesariny de Vasconcelos, poeta e pintor, morreu a 26 de Novembro de 2006, em Lisboa, de cancro.

Mário Cesariny de Vasconcelos, poeta e pintor, morreu a 26 de Novembro de 2006, em Lisboa, de cancro. Tinha nascido na mesma cidade a 9 de Agosto de 1923. Os dois textos que se seguem foram publicados no

Público.

Poeta genial

Luís Miguel Queirós

Público, 27 de Novembro de 2006

Foi o expoente máximo do surrealismo português. Esta declaração irá fatalmente abrir quaisquer verbetes que a futura historiografia literária venha a dedicar a Mário Cesariny. No entanto, na sua factualidade, esta associação ao surrealismo acaba por impedir que se diga desde logo o óbvio: que estamos perante um dos nomes cimeiros da poesia portuguesa de todos os tempos. E que não deixaria de o ser mesmo se rasurassem da sua obra todos os poemas (e eles existem) indiscutivelmente surrealistas. Em sentido estrito, já que no peculiar sentido lato em que o entendeu o próprio Cesariny - para quem o surrealismo, mais do que ter tido precursores, sempre existiu -, pode-se lá pôr, ou tirar, mais ou menos tudo o que se queira.

Se Cesariny foi um grande poeta, foi-o principalmente pelas razões pelas quais os grandes poetas costumam sê-lo: a capacidade de inovar, um domínio absoluto da língua, um conhecimento profundo da tradição literária, uma voz singular e uma imaginação prodigiosa, para referir apenas algumas das suas virtudes mais evidentes. No seu caso, é ainda legítimo acrescentar que foi um génio, desde que entendamos que a palavra não se destina a superlativizar a qualidade do que escreveu, mas apenas a apontar para determinadas características da sua criação. Quando lemos alguns dos mais notáveis poemas de Cesariny, damos por nós a perguntar: "Mas de onde é que raio veio isto?" E suspeitamos de que nem o autor faria a menor ideia. É talvez por aqui que passa aquilo a que chamamos génio, ou inspiração. Acresce que, ao contrário de outros poetas, que nunca esconderam que a sua obra devia pelo menos tanto à transpiração como à inspiração - não foi por acaso que Carlos de Oliveira compilou os seus poemas reescritos sob o título

Trabalho Poético -, Cesariny sempre entendeu a poesia como uma espécie de possessão mediúnica, e daí a sua simpatia por poetas nos quais pressentia essa afinidade, como Gomes Leal, Pascoaes ou Sá-Carneiro, a quem, já em 1952, dedicou um poema cujos versos finais poderiam bem servir de epitáfio a si próprio: "desembarcou como tinha embarcado//Sem Jeito Para o Negócio."

É também essa convicção de que não vale a pena escrever poesia por determinação ou disciplina que justifica o facto de Cesariny ter passado longos anos quase em silêncio, após ter publicado o essencial da sua obra nos vinte anos que vão de

Discurso Sobre a Reabilitação do Real Quotidiano (1952) a

19 Projectos de Prémio Aldonso Ortigão seguidos de Poemas de Londres (1971).

Todavia, também a imagem de Cesariny como protótipo do poeta inspirado, demiúrgico, acaba por ser redutora, quer porque deixa na sombra uma mestria técnica que, além de talento, implicou seguramente muito trabalho, quer pelo visível diálogo que muitos dos seus poemas travam com a obra de outros poetas, e em especial com a de Fernando Pessoa, desde o

Louvor e Simplificação de Álvaro de Campos, de 1953, ao seu último livro,

O Virgem Negra (1989; 2ª edição aumentada, 1996), uma desvairada, e muitas vezes brilhante, paródia à mitificação da obra e persona pessoanas.

O mágico das mãos de ouro

Cesariny publicou o seu primeiro livro,

Corpo Visível, em 1950, e muitas das marcas posteriores da sua poesia estão já aqui: a centralidade do corpo, a revolta contra as convenções, a alternância de imagens inesperadas e de descrições realistas, uma vigilância prosódica eficaz a ponto de não se dar por ela. Já o humor, absurdo, sarcástico ou negro, que será uma outra característica fundamental da sua poesia, só aparece dois anos depois, com os inventários de

Discurso Sobre a Reabilitação do Real Quotidiano: "(...) a outra viagem por mar/ o jovem que já é livreiro/ a camionete a esmagar/ o túmulo de Sá-Carneiro (...)."

Mas é com

Manual de Prestidigitação (1956) que Cesariny passa a ser, não apenas um executante hábil e original do surrealismo, mas um poeta maior ao qual já não faz sentido acrescentar quaisquer rótulos, mesmo que seja ele a colá-los. Pense-se, por exemplo, no "discurso ao príncipe de epaminondas, mancebo de grande futuro", um desses poemas a propósito dos quais é difícil não falar de génio: "Despe-te de verdades/ das grandes primeiro que das pequenas/ das tuas antes que de quaisquer outras/ abre uma cova e enterra-as/ a teu lado (...)". Neste e no livro seguinte,

Pena Capital (1957), reúnem-se alguns dos seus melhores poemas: "Vinte quadras para um dadá", "a um rato morto encontrado num parque", "o jovem mágico", "you are welcome to elsinore" ou "a antonin artaud". Foi também neste período, apesar de todas as suas cirúrgicas sabotagens do que ameaçava poder tornar-se grandiloquente, que Cesariny esteve mais perto de estar dentro dessa Literatura da qual sempre afirmou que se devia procurar sair.

Até ao final dos anos 50, edita ainda

Alguns Mitos Maiores Alguns Mitos Menores Propostos à Circulação Pelo Autor e

Nobilíssima Visão, com a sua cáustica "Litania para os tempos de revolução" - "Burgueses somos nós todos/ desde pequenos/ burgueses somos nós todos/ ou ainda menos (...)".

No mesmo ano em que publica

Planisfério e Outros Poemas (1961), sai ainda

Poesia (1944-55), o primeiro dos sucessivos momentos em que baralhará toda a sua obra anterior, revendo, rasurando e acrescentando poemas, e mudando-os de uns livros para outros. Um jogo que prossegue em

Burlescas, Teóricas e Sentimentais (1972) e nas

Obras de Mário Cesariny que a Assírio & Alvim vem publicando desde 1980, e que agora se tornaram, por razões de força maior, a fixação definitiva da sua obra poética.

Em 1965, sai

A Cidade Queimada, cujo conjunto "O Navio de Espelhos" é outro ponto alto da sua poesia, e em 1971 publica

19 Projectos de Prémio Aldonso Ortigão seguidos de Poemas de Londres. Pertencem a esta última série poemas como o "estranho soneto de amor outra coisa" ou esse magnífico "shafftsbury avenue", que abre com o verso "Vi um anão inglês e fiquei perturbado".

A reedição da sua poesia na Assírio & Alvim inicia-se com

Primavera Autónoma das Estradas (1980), que, a par de um grande número de dispersos, recolhe ainda um conjunto significativo de inéditos. E em 1989 Cesariny regressa com o já referido

Virgem Negra, um livro divertidíssimo e ligeiramente

hardcore, onde pega em poemas célebres de Pessoa e os cesariniza. Nada de muito diferente do que fez com o surrealismo, com as redondilhas populares, ou com tudo aquilo em que tocaram as mãos de ouro deste jovem mágico.

Viveu à altura da obra e a obra esteve à altura da vida

Alexandra Lucas Coelho

Público, 27 de Novembro de 2006

Mário Cesariny não quis ser cremado. "Tinha lido num tratado de esoterismo que, a haver alguma coisa depois da morte, seria a partir do osso sacro", recorda o amigo José Manuel dos Santos. O osso na base da coluna é o centro da energia espiritual, dormente na maioria das pessoas até à morte, segundo crenças esotéricas. Cesariny não era crente nem ateu. Como todos os não tranquilizados, "olhava para a morte com grande gravidade", sem qualquer certeza. E "em caso de dúvida, o melhor é não arriscar". Que a oportunidade não se perdesse.

Assim viveu.

E até ao fim disse as coisas mais extraordinárias, porque - como distingue outro amigo muito antigo, Vítor Silva Tavares - não era um "poeta por escrito", mas um "poeta integral, irradiante".

De raríssimos (quem mais?) se poderá dizer "viveu à altura da obra, e a obra esteve à altura da vida", como dele diz José Manuel dos Santos. Este ex-assessor cultural de Mário Soares e Jorge Sampaio conheceu Cesariny num café, andava o poeta pelos 50 anos. Primeira e definitiva impressão: "Grande vitalidade, grande graça, uma inteligência fascinante, uma cultura absolutamente original. Nunca o ouvi dizer um lugar comum, no amor ou na política, algo que já se tivesse ouvido."

Era isto na Lisboa da rua, dos cafés, de que Cesariny tanto sentia falta ultimamente, ele que nunca escreveu em casa.

Nascido a 9 de Agosto de 1923 por acaso na Damaia - onde os pais estavam a passar férias numa quinta -, Mário Cesariny é lisboeta de raiz, crescido na Rua da Palma, junto ao Martim Moniz. "O pai era ourives e queria que ele fosse ourives", lembra Manuel Rosa, seu editor, na Assírio & Alvim. "Tinham uma relação péssima. O Mário não era o filho que ele queria."

Da adoração pela mãe e da repulsa pelo pai fala Cesariny no filme-documentário

Autografia, de Miguel Gonçalves Mendes.

Único rapaz depois de três raparigas (Henriette, Luísa e Carmen, esta última ainda viva), Cesariny, que era aluno de Fernando Lopes-Graça na Academia dos Amadores de Música, aproveitava o piano em que as irmãs estudavam, como as meninas prendadas da época. Mas a medo, antes que o pai chegasse.

"Um dia o pai apanhou-o e fechou-lhe o piano com toda a força sobre as mãos", conta Manuel Rosa. "E o Lopes-Graça achava que ele tinha um talento extraordinário. O Mário sabia todos os poemas de cor, e só os escrevia depois de os ter na cabeça, e esta memória extraordinária também a tinha para a música."

Em 2000, quando o Salão do Livro de Paris teve Portugal como país-tema, Cesariny, que não fôra integrado na delegação oficial, viajou com Manuel Rosa e Manuel Hermínio Monteiro, da Assírio & Alvim. "A certa altura havia uma recepção na embaixada. Mas perdemo-nos, de carro, à volta do Arco do Triunfo, a chover, de noite. E o Mário, que não queria ir ao Salão, muito contente, ia dizendo poemas do Apollinaire, do Baudelaire e cantava canções anarquistas." As canções que os operários do pai lhe cantavam, em miúdo.

O não-funcionário

Além da música, Cesariny frequenta o Liceu Gil Vicente e a António Arroio (onde são seus colegas Cruzeiro Seixas, Júlio Pomar, Pedro Oom ou Vespeira, companheiros de tertúlia no café Herminius).

Academicamente, é tudo. "O pai, que tinha uma amante, saiu de casa, foi para o Brasil e deixou-os numa miséria atroz", diz Manuel Rosa. "O [poeta] Pedro da Silveira, que então tinha um jornal desportivo,

O Volante, é que arranjou maneira dele lá trabalhar."

E assim, durante um ano, Cesariny é jornalista desportivo. Um dos poucos "ganchos" que teve, sublinha Silva Tavares. "Numa altura em que todos tinham empregos ou passaram pela publicidade, recusou ser poeta funcionário. E muito menos mercenário. «Ganhar, sim, mas pouco» é uma frase que ele dizia e que tomei como luz central da minha vida. «É de alguma debilidade económica que vem a minha liberdade.»"

Publica o primeiro poema, "O Corpo Visível", aos 27 anos, mas desde os 19 que escreve, desenha e pinta. Com uma passagem pelos neo-realistas e pelos comunistas, com quem rompeu rapidamente. "Ele tinha grande prevenção contra o comunismo", conta José Manuel dos Santos. "Dizia que se houvesse um comunismo em que nada fosse de ninguém e todos fôssemos de todos, seria comunista. Mas, tal como o comunismo se realizara, não tinha dúvidas de que era uma coisa monstruosa."

A sua verdadeira revolução seria o Surrealismo. Numa viagem a Paris em 1947 conhece André Breton e outros do grupo francês e nesse ano é um dos fundadores do Grupo Surrealista de Lisboa. Sai no ano seguinte para fundar o alternativo Os Surrealistas.

A partir do que o poeta contava e do que testemunhou depois, José Manuel dos Santos reconstitui o quotidiano de Cesariny, entre esses anos 40 e os anos 80, grande fumador que nunca bebeu álcool e se alimentava austeramente.

Já a viver na casa da Palhavã onde morreu, levantava-se pela hora de almoço, comia algo leve, e ia para o atelier na Calçada do Monte, entre a Graça e o Martim Moniz. "Era num pátio com operários de toda a espécie, absolutamente de acordo com o que ele era. Não um lugar recatado, ao lado de outros pintores, mas dentro da vida, no espírito surrealista."

Quando Vieira da Silva fez o cartaz do 25 de Abril com o verso de Sophia A poesia está na rua, lembra José Manuel dos Santos, Cesariny escreveu à pintora a dizer: "Sempre esteve."

As noites do Rei Mar

À hora de jantar voltava a casa para comer algo e saía, ruas, cafés e bares, até altas horas. Eram as tertúlias, a do café Gelo, a do Lisboa, na baixa. E o engate. "Aquilo acabava sempre no Rei Mar, um café-taberna na Rua das Pretas. Tudo lá parava, prostitutas, travestis, todos os marginais e toda a tropa que andava ao engate, fuzileiros, comandos, paraquedistas..." Os predilectos de Cesariny, marinheiros. "O mar, a farda, o sentido de aventura, tudo o encantava. Tinha um fascínio pela marinha, sabia os termos todos e usava-os na obra."

Volta e meia a polícia de costumes detinha-o por vagabundagem, mas preso, preso, só uma vez em Paris, apanhado num cinema com um rapaz e acusado de actos "indecentes". "Atordoado", conta Manuel Rosa, esteve um mês na cadeia sem se lembrar de ligar por exemplo a Vieira da Silva. Só quando a notícia correu, a pintora soube e fez alguns telefonemas. Cesariny foi solto, com a condição de em Lisboa se apresentar regularmente no Governo Civil. Um enxovalho semanal.

Tivera a sua fase grega, "de muito amor e pouco sexo" - terá sido o seu grande amor, com um homem das artes nortenho, que lhe escreveu uma carta em 1950, que acabou na PIDE.

Depois o amor passou a durar uma hora, mas nessa hora era tudo.

Os seus grandes poemas foram escritos no tempo incandescente do amor. A poesia acompanhava o corpo. Uma "necessidade absoluta".

Seguiram-se décadas de quase só pintura. Nunca escreveu para manter o nome.

Vítor Silva Tavares, que lhe editou

A Intervenção Surrealista e

A Cidade Queimada, sentiu a sua morte como "uma amputação". "É um bocado de mim que vai." E tiveram brigas sérias de que depois se riram, sem que a admiração descesse um pouco que fosse. "Nele não há ruptura entre vida e obra. Onde quer que aparecesse era a aura do poeta. Um príncipe num país de medíocres, um homem magnífico."

Ontem, a este "amigo-amigo, com amizade amorosa, sexo à parte", a primeira coisa que veio à cabeça quando soube foi a frase de um anúncio, adaptada: "«Uma chama viva, onde quer que esteja.» Só o corpo de Cesariny morreu hoje."